A plated serving of my own version of Lobster Macaroni and Cheese, described in the recipe at the bottom of this page.

SECTIONS

- Introduction

- Examining The Conjecture

- Historical Origins

- Sidebar: Live vs. Canned Seafood

- First Known Instance

- Recipe Ingredient Details

- Recipe

- Other Recipe Versions

- Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

Like many popular dishes, Lobster Macaroni & Cheese appears to be a relatively recent development. It’s served in numerous restaurants in Maine as a relatively high-end dish, made with Cavatappi or “corkscrew” pasta that’s folded with a flavorful, creamy, somewhat decadent cheese sauce, and topped with 4 to 6 ounces of fresh lobster meat that’s likely only been fished within the previous 24 hours. The dish can also be found at various restaurants along the entire east coast, at tourist spots such as Put-In-Bay, a resort island community in Lake Erie northeast of Toledo, Ohio, and as far away as Seattle and Los Angeles, with many menus touting Maine Lobster Macaroni & Cheese.

The Lobster Macaroni & Cheese from McSeagull’s in Boothbay Harbor, Maine, on May 11, 2020. During the COVID-19 shutdown at that time, the dish was only available for curbside pickup.

Bring the dish up with someone of Italian descent, however, and prepare for fireworks. Seafood and cheese apparently must never be used within the same dish. This apparent gaffe on the part of patrons is such that discussions on the web site Chowhound in March of 2007 indicated some Italian restaurants won’t even allow diners to request shredded Parmesan on their Shrimp Linguini.

We’ll first look at online conjecture of possible histories, and what’s faulty in those discussions. We’ll then go back to the late 1800s for some earlier but similar dishes, and examine how they evolved towards Lobster Macaroni & Cheese. Finally, we’ll look at the first known instance of the codified dish, and walk through the component parts of a complete recipe.

EXAMINING THE CONJECTURE

Discussions online tend to bring up various possible histories, including conjecture about Lobster Macaroni & Cheese being the result of further development of the recipes for Lobster Newburg or Coquilles St. Jacques. In examining this conjecture we find that Lobster Newburg originated with the Delmonicos. Immigrants from Switzerland in the 1820s, they opened their first eatery in New York in 1827. It was in the early 1890s that patron Ben Wenberg demonstrated to Delmonico’s Chef a method of preparing lobster he’d observed in South Africa. This dish was then offered in the restaurant as “Lobster Wenberg” … That is, until Mr. Wenberg started a brawl within Delmonico’s. The dish was then renamed “Lobster Newberg.” [Levinson, 1964]

However, a look at various preparations of Lobster Newberg reveals a lack of cheese or even pasta in the dish. This includes the 1921 edition of the Boston Cooking School Cook Book, which included separate preparations for Lobster à la Delmonico and Lobster à la Newburg [sic], as well as Clams à la Newburg and Shrimp à la Newburg. [Farmer, 1921]

Recipes for Coquilles St. Jacques, a classic French King Scallop dish with oysters, shrimp, mushrooms and onions in a butter sauce with grated cheese, shows up in American cookbooks as early as [Kirk, 1947], baked in either greased scallop shells or individual ramekins. Later versions present the dish as a “Real Fine Scallop Casserole” without oysters, shrimp, mushrooms or onions, and baked in a single glass casserole dish. [Shibles, 1975] Again however, no lobster or pasta are involved.

There’s also mention of a dish from Thomas Keller’s “French Laundry Cookbook” presenting lobster and pasta in a mascarpone sauce. This turns out to be Keller’s Butter-Poached Maine Lobster with Creamy Lobster Broth and Mascarpone-Enriched Orzo. With “Macaroni and Cheese” above the recipe’s title, Keller wrote the following in the description for the recipe:

“We serve so much lobster at the restaurant that creating new lobster dishes is always an exciting challenge. I used to do an actual gratin with lobster and macaroni, but now I use orzo with mascarpone, the lobster on top, and Parmesan crisps – an echo of the crisp texture of a traditional gratin dish. The coral oil rings the orzo for bright color, and I finish the plate with chopped coral.” [Keller, 1999]

The only issue with this particular recipe and its stated history are that they were developed decades later than the first-known version of the codified dish.

Even later than [Keller, 1999], the New York Times presented an implied origin of Lobster Macaroni and Cheese as recently as 2011. The implication was that the invention of the dish was related to a “record haul” by Maine lobstermen that year, and that further markets needed to be developed:

“(A) handful of new companies are producing packaged lobster convenience foods, like lobster macaroni and cheese, with the goal of selling them in grocery stores nationwide … One such company is Calendar Islands Maine Lobsters in Portland, which will introduce its lobster mac and cheese and lobster pizza at the International Boston Seafood Show next month … ‘We’re trying to put lobster into markets where it hasn’t been,’ said John Jordan, the company president, ‘in forms where people can just buy it and put it in the oven and have an easy meal.'” [Goodnough, 2011]

The history of Lobster Macaroni & Cheese as a codified dish goes back more than a century, outside of the suggested dishes, chefs, or markets. We also find that cheese and seafood have gotten along quite well in Italian dishes for quite some time, regardless of cultural thoughts and emotions about the subject. It was a well-known Italian restaurant in New York City that appeared to codify the dish in the early-to-mid-1900s, a restaurant not previously mentioned. But even that dish had its predecessors.

HISTORICAL ORIGINS

In 1888 Harriet A. De Salis published a small cookbook in both London and New York, “Oysters à la Mode: The Oyster and Over 100 Ways of Cooking It.” Split between pages 42 and 43 of this book was a recipe for Sorrento Oysters. This appears to be an early upscale version of the dish we know today, if not the earliest, combining cooked macaroni with oysters, Parmesan, and cream, then browning individual servings in scallop shells for an elegant presentation.

Sorrento Oysters

Stew some macaroni in gravy till tender, seasoning with cayenne and salt to taste; then take equal parts of oysters and macaroni, and chop them up together, and mix well in a stewpan with some grated Parmesan cheese, a little butter, and enough cream to moisten all sufficiently; stir it on the fire till hot, then fill your scallop shells with the mixture and brown them before the fire. Serve immediately. [De Salis, 1888]

Interestingly enough, six years earlier the same publisher of [De Salis, 1888] had published “Cookery and Housekeeping, A Manual Of Domestic Economy for Large and Small Families” by a Mrs. Henry Reeve. The work contained the following recipe, an obvious predecessor to the later Sorrento Oysters but lacking cheese:

Oysters and Macaroni

Lay some stewed macaroni in a deep dish; put upon it a thick layer of oysters, bearded, and seasoned with cayenne pepper and grated lemon rind; add a small teacupful of cream; strew breadcrumbs over the top and brown it in a pretty quick oven. Serve hot, with a piquante sauce. [Reeve, 1882]

The lack of cheese in this previous version implies De Salis was the originator of the version combining shellfish with Macaroni & Cheese.

A variation of De Salis’ Sorrento Oysters then shows up in [Farmer, 1896] as Oyster and Macaroni Croquettes. In this version a similar mixture made with Farmer’s Thick White Sauce is cooled, shaped into patties, dipped in crumbs, egg, then crumbs again before being fried in fat. However, this variation of Farmer’s does not appear in her earlier work published in 1884. The implication here is that Farmer derived this 1896 version of her recipe from [De Salis, 1888].

Oyster Macaroni and Cheese is still a popular dish. It shows up as a recipe in numerous locations in a web search, and is served at oyster festivals, restaurants, and from food trucks, as well as as a deep-fried snack or appetizer similar to Farmer’s version.

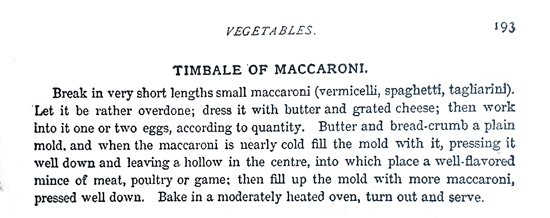

A recipe for Timbale of Maccaroni [sic] was included in both The White House Cook Book of 1887 and it’s sister publication, The Presidential Cook Book, published in 1895 as “adapted from” the former.

Timbale of Maccaroni

Break in very short lengths small maccaroni (vermicelli, spaghetti, tagliarini). Let it be rather overdone; dress it with butter and grated cheese; then work into it one or two eggs, according to quantity. Butter and bread-crumb a plain mold, and when the maccaroni is nearly cold fill the mold with it, pressing it well down and leaving a hollow in the center, into which place a well-flavored mince of meat, poultry or game; then fill up the mold with more maccaroni, pressed well down. Bake in a moderately heated oven, turn out and serve. [Gillette, 1887] [Gillette, 1895]

It’s important to note that the term “macaroni” hasn’t always been as narrowly defined as it has been in recent times. Some references such as [Kirk, 1947] narrowed the focus in the first half of the 20th century. Other references even as late as [Wise, 1954] described macaroni in these terms:

“There are practically all shapes and sizes of macaroni, some formed into long straight sticks, some in small elbows, sea shells of various sizes, baskets and alphabets, all, however, having the same food value.”

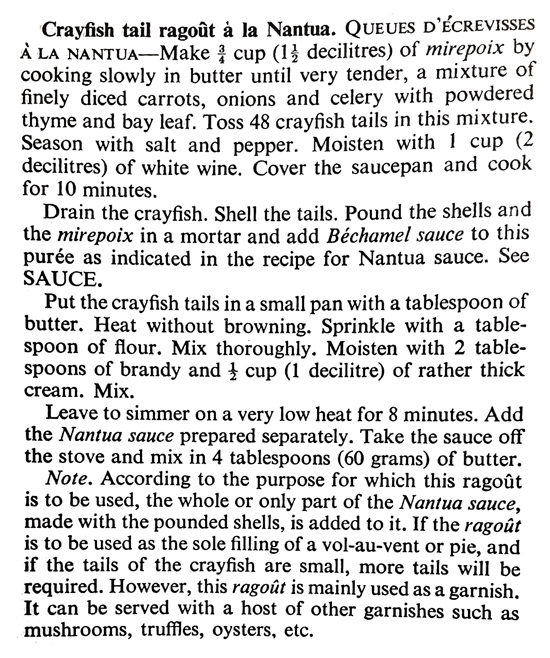

The nearest known mention of a dish similar to Lobster Macaroni and Cheese, which also happens to be quite similar to Timbale of Maccaroni, shows up in the first English translation of “Larousse Gastronomique” in 1961. Within the “Introduction to the English Language Edition” it reads, “As editors our chief aim has been to present as faithful a version as possible of the original work.” What this indicates is that the recipe to be discussed, Macaroni à la Nantua, was in the original 1938 edition.

Macaroni à la Nantua

Macaroni à l’italienne served in a pie crust of lining pastry baked blind (empty) with alternate layers of Crayfish tails à la Nanuta*. [Montagné, 1961]

As described in [Montagné, 1961], Macaroni à l’italienne is a basic Macaroni and Cheese dish of macaroni, grated Gruyére and Parmesan cheeses, butter, salt, and grated nutmeg. What’s interesting though is that this is then layered with Crayfish tails à la Nanuta. Without getting into the further details of this preparation, the rather lengthy recipe for Crayfish tails à la Nanuta also references two other recipes within the book.

One other recipe bears mention within these developments. Beginning with her self-published edition of only 3,000 copies in 1931, Irma Rombauer included a recipe for Spaghetti with Sea Food (American Version) in her now highly popular cookbook The Joy Of Cooking. Immediately before this recipe within the cookbook she included Italian Spaghetti with Sea Food. A basic spaghetti dish topped with shredded Parmesan cheese, the ingredients for a tomato sauce were stirred together with “1 cupful of cooked shredded anchovies, ham and tongue, or 1 cupful of cooked seafood” before being combined with the cooked spaghetti.

The recipe for Spaghetti with Sea Food (American Version) that followed combined a roux with tomato soup with a half-pound of cheese before the “sea food” was added. It’s presented here in the book’s signature style.

SPAGHETTI with SEA FOOD

(American version)

About 2-1/2 quarts

Cook by the rule on page 93,

1/2 pound spaghetti (2 cups)

Heat the contents of:

1 (10-1/2 oz.) can condensed tomato soup

Melt in a saucepan over slow heat:

4 tablespoons butter

Add and cook for one minute:

1/4 cup or more chopped onion

1/4 cup or more green pepper

Stir in until blended:

4 tablespoons flour

Stir in slowly:

2 cups Stock or Stock Substitute (page 52) or milk

When the sauce is thick, add very slowly, stirring constantly:

The hot tomato soup

1/2 pound cheese, diced

When the cheese is melted add:

1/2 pound diced lobster, crab or shrimp

and the boiled, drained and rinsed spaghetti. Add seasoning if required.

This dish may be prepared in advance.

To reheat place it over boiling water. [Rombauer, 1931]

SIDEBAR: LIVE VS CANNED SEAFOOD

The locations are interesting for the earlier recipes listed above:

- Sorrento Oysters, 1888: London, England

- Oyster and Macaroni Croquettes, 1896: Boston, Massachusetts

- Timbale of Maccaroni, 1887: Washington, DC

These and other seafood recipes which hadn’t specified canned oysters, lobsters, crab, clams, etc., were developed in or near coastal communities where live seafood would have been available. Until the 1900s, only canned seafood would have been available more than a few hundred miles from the coasts. [Dueland, 1973]

William Underwood opened his vegetable, condiment, and sauce cannery in Boston in the 1820s, expanding to offer canned lobster by 1836. This production developed in other Maine communities as well. According to the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath:

“In the letter nineteenth century, canning of lobsters had overtaken and passed live marketing in volume … The 1880 statistics show that twenty-three Maine factories were active … Packing 2 million pounds of meat took almost 9.5 million pounds of lobsters. By contrast, the live market consumed little more than 4.7 pounds that year … Of the twenty-three canneries in Maine in 1880 … ten prepared lobsters only; six, lobsters and mackerel; one, lobsters and clams; and six, lobsters, mackerel and clams; one of the last also put up salmon, fish-chowder and clam-chowder … By 1880, 800 people worked in Maine lobster canneries.” [Martin, 1985]

The late 1800s saw shipments of live lobsters in barrels layered with ice and seaweed from Maine to King George III of England, and to Emperor Napoleon of France, as well as a 54-day voyage for twelve lobsters in saltwater tanks from England to New Zealand. Three of those twelve lobsters did not survive. [Dueland, 1973]

The development of the “lobster pound” in 1875, the first having nine acres of tidal flow to keep lobsters alive during off-seasons, helped in having enough live lobsters to ship nationwide by rail and around the world by sea. Maine then had nine lobster pounds by 1898. 1892 saw the development of the “steam smack”, the first being a 49-foot steamer with an experimental “well” for containing live lobsters in seawater for long-distance shipment. Other shippers then followed suit, with “smackers” being able to pull into harbors for direct sale to residents and commercial operators. By the early twentieth century, canning had fallen off in the U.S. due to increasing regulations and the expansion of the live market. By the end of WWII, air shipments of live lobsters became practical, and the majority of lobster canneries had either ceased operation or converted over to other products. [Martin, 1985]

Although canned lobster meat is still available from of a few canneries near the coasts, the flavor, texture, and overall quality in recipes such as Lobster Macaroni and Cheese benefit from using freshly-cooked live lobster in the dish.

FIRST KNOWN INSTANCE

Combining lobster with pasta instead of oysters or meats appears to have first occurred in the kitchen of a rather well-known Italian restaurant in New York City in a dish quite similar to what is served today. Ironically, the Italian immigrants there combined cheese and lobster in a manner that other Italians today claim cannot be allowed.

Luisa “Mother” Leone opened Mamma Leone’s restaurant with her husband Gerome’s blessing (at family friend Enrico Caruso’s urging) on April 27, 1906, with 20 seats. Over time, and with a move to 239 W. 48th St. (now an alley next to La Masseria), the restaurant grew to seat 1,500, serving 6,000 covers on busy evenings. Gerome died in 1914. Luisa died on May 4, 1944, and son Gene bought his sister out in 1952 to become sole owner. The restaurant served Eisenhower, George M. Cohan, W.C. Fields, Victor Herbert, Liberace, and countless others. Chef Gene sold the restaurant to Restaurant Associates on June 9, 1959. Restaurant Associates operated Mamma Leone’s until closing it for good on January 10, 1994.

Luisa “Mother” Leone opened Mamma Leone’s restaurant with her husband Gerome’s blessing (at family friend Enrico Caruso’s urging) on April 27, 1906, with 20 seats. Over time, and with a move to 239 W. 48th St. (now an alley next to La Masseria), the restaurant grew to seat 1,500, serving 6,000 covers on busy evenings. Gerome died in 1914. Luisa died on May 4, 1944, and son Gene bought his sister out in 1952 to become sole owner. The restaurant served Eisenhower, George M. Cohan, W.C. Fields, Victor Herbert, Liberace, and countless others. Chef Gene sold the restaurant to Restaurant Associates on June 9, 1959. Restaurant Associates operated Mamma Leone’s until closing it for good on January 10, 1994.

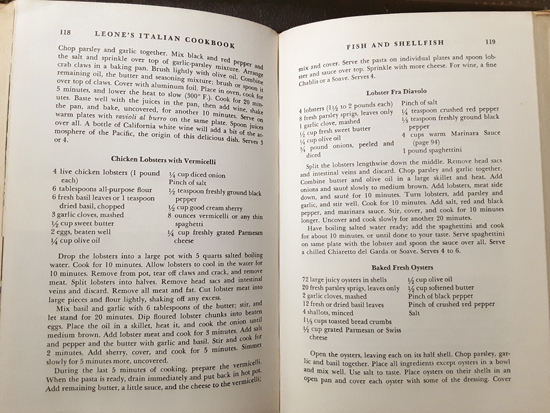

In 1967 Chef Gene published “Leone’s Italian Cookbook” containing the restaurant’s story, as well as more than 300 recipes served in the restaurant from 1906 to 1959. Among those recipes was Chicken Lobsters with Vermicelli. [Leone, 1967]

The recipe for Chicken Lobsters with Vermicelli as printed in Leone’s Italian Cookbook. The recipe for the restaurant’s popular Lobster Fra Diavolo was also included on page 119, on the right.

Below is a downloadable copy of Mamma Leone’s Chicken Lobsters with Vermicelli.

A couple of points about the recipe are, firstly, that it specifies vermicelli or “a thin spaghetti.” Moving to a style of macaroni noodle would then provide more body to the dish, creating more of a comfort food. Secondly, the procedure includes a style of pan-frying of the cooked lobster meat. As Lobster Macaroni & Cheese traditionally uses lobster meat coated with either warm clarified butter or some of the cheese sauce intended for the noodles, the transition from the Leone recipe to the Maine specialty becomes rather straightforward.

It’s possible Mother Leone’s Chicken Lobsters with Vermicelli wasn’t the first instance of this dish. It’s also unknown whether she or her son Gene developed it, when it may have first been served in the almost six decades the restaurant was open, or if someone had taught it to them similarly to how Wenberg had taught his dish to the Chef at Delmonico’s. However, Chicken Lobsters with Vermicelli is certainly a precursor to what restaurants in Maine and elsewhere are serving today.

RECIPE INGREDIENT DETAILS

The ingredients needed for the recipe below, minus the milk and the cooked lobster meat.

“Cellentani™” is a Registered Trademark of Barilla, and is the original corkscrew pasta. Because of this trademark, other brands market their versions of the pasta under the generic name Cavatappi.

One of the more popular pastas for a dish such as Lobster Macaroni & Cheese is what’s known as “cavatappi” or “corkscrew” pasta. “Cellentani™” was originally developed by Barilla in the 1960s. Named for Italian pop singer Adriano Celentano, it’s a hollow spiral pasta that’s an evolution of “fusilli bucati corti”. [Barilla, 2013] However, “Cellentani™”is a Registered Trademark of Barilla, which is why other manufacturers use the names “cavatappi” or “corkscrew”.

You can also use medium shells (aka “mezzo conchiglie”), elbow macaroni (aka “Gomiti” or “Chifferi”), or a Penne or Pipette pasta if cavatappi is unavailable.

How do you determine how much lobster to cook? According to Lobster Anywhere the following yields are standard:

Yield percentages

- 15% Lobster Tail

- 10% Claw Meat

- 3% Knuckle Meat

- 2% Leg Meat

| Lobster Sizes | Weight | Hard Shell Meat Yield (22%) | Soft Shell Meat Yield (17%) |

| Chickens or Chix | 1 lb | 3.36 oz | 2.72 oz |

| Quarter | 1.25 lb | 4.2 oz | 3.4 oz |

| Halves | 1.5 lb | 6.7 oz | 4.08 oz |

| Deuces | 2 lb | 6.72 oz | 5.4 oz |

| Jumbos | 3 lb | 10.08 oz | 8.18 oz |

| Large Jumbos | 6 lb | 1.28 lb | 1.02 lb |

Mr. Sea’s Lobster Pound in Lewiston, Maine, one of my favorite sources for fresh lobster.

Left: The steamer in front of Mr. Sea’s Lobster Pound, with the sign showing per-pound prices on August 21, 2020. (Note: These prices change daily.)

Left: The steamer in front of Mr. Sea’s Lobster Pound, with the sign showing per-pound prices on August 21, 2020. (Note: These prices change daily.)

Besides knowing what size lobsters to get based on how many people you’re serving and whether the lobsters are soft-shell or hardshell, it’s important to get the freshest lobster possible. Many lobster pounds and some fishing companies in Maine will ship live lobsters overnight for a fee, taking two or three day for longer distances. These are still likely fresher than grocery store lobsters.

In Maine I’ll get fresh lobsters from a place such as Mr. Sea’s Lobster Pound in Lewiston. Mr. C. himself sources these lobsters and other crustaceans from fishermen during multiple trips to the docks every day. His daughter Mjae is now the owner of the Pound, and makes sure her staff are all properly trained in preparations of steamed lobsters, fried whole belly clams and calamari, and other fresh seafood. Their expertise in this area, coupled with current market prices, meant that the two 1 lb freshly-fished lobsters I ordered steamed for this recipe on August 21, 2020, came to $13. (Note that lobster prices change daily and seasonally. The prices I paid will be different on any other given day.)

My two 1 lb lobsters prior to going into Mr. Sea’s steamer.

The cooked lobsters, ready for me to pick the meat from them.

RECIPE

Maine-style Lobster Macaroni & Cheese

Ingredients

- 1 lb cavatappi or Cellentani™ (a.k.a. “corkscrew”) pasta, dried see Notes below

- 3 cups milk, whole or raw raw milk is legal for sale in Maine

- 6 Tbsp butter not margarine

- 6 Tbsp Wondra™ quick-mixing all purpose flour

- 3/4 tsp dry mustard

- 1/2 cup Vermont sharp cheddar cheese, finely shredded

- 1/2 cup Gouda cheese, finely shredded

- 1/2 cup Gruyere cheese, finely shredded

- sea or Kosher salt

- white pepper, ground

- 2 cups Parmesan cheese, finely shredded for topping

- 1 lb lobster meat, warm

Instructions

- Prepare the pasta according to its instructions, ensuring it’s al dente when finished.

- While the pasta is cooking, cut the butter into pats about 1/2 Tbsp each.

- Add the milk, pats of butter, and flour to a 2-quart saucepan and whisk well till the flour is dissolved. Bring to a boil over medium heat, stirring constantly.

- Allow the sauce to boil for 1 minute, stirring constantly, reducing the heat as needed to prevent scorching.

- Remove the sauce from the heat. Whisk in the dry mustard, and the Vermont sharp cheddar, Gouda, and Gruyere cheeses, then whisk until smooth.

- Add the sea or Kosher salt and white pepper to the sauce to taste.

- Drain the pasta (be sure to toss it to get all the water from inside the noodles) and pour it into a large mixing bowl.

- Fold a serving-spoon portion of the sauce with the warm lobster, enough to sauce the lobster meat with a thin coating.

- Fold the remainder of the cheese sauce into the pasta.

- Plate the Mac & Cheese topped with the sauced lobster meat, followed by the shredded Parmesan cheese.

Notes

- Some cavatappi packages, especially store branded, are 12 ounces instead of 16. This recipe is for 16 ounces of dry cavatappi. If the package is 12 ounces, it's better to buy four of them and make three 16 ounce containers than it is to adjust the recipe for the cheese sauce for a 12 ounce package. The other dry noodles will keep for a later batch anyway.

- You can also use medium shells (aka "mezzo conchiglie"), elbow macaroni (aka "Gomiti" or "Chifferi"), or a Penne or Pipette pasta if cavatappi is unavailable.

- To rejuvinate leftovers of this dish, stir in about 1/2 cup whole milk for half what the recipe makes, and reheat in a pot over medium heat until just heated through. Do not microwave, as doing so will destroy the texture.

- This recipe was adapted from the cheese sauce recipe on the Wondra™ container.

- “Wondra™” is a Registered Trademark of General Mills.

- "Cellentani™" is a Registered Trademark of Barilla

OTHER RECIPE VERSIONS

Two cheeses from Cabot Creamery in Cabot, Vermont, that would be good in this dish. The Wickedly Habanero is specified in the recipe for Spicy Lobster Mac and Cheese from Foodness Gracious, linked below.

These are just a few other versions I find interesting in some manner. First are a few variations from Cabot Creamery in Cabot, Vermont, in my opinion one of the better creamery coops in New England. Their quality is why I specify their sharp cheddar in my own recipe.

- Lobster Macaroni and Cheese, Chef Leo Ledoux, Mio Bistro (now closed), Dorset, Vermont

- Lobster Macaroni and Cheese, White Mountain Hotel and Resort, North Conway, New Hampshire

- Lobster Macaroni and Cheese with Cheddar Cornbread Topping, Chef Jimmy Kennedy, Cabot Creamery

The following are listed alphabetically, with no preference intended, only that they sound as though they’re worth a try.

- Cannabis-Infused Lobster Mac and Cheese, The Manual

Includes cannabutter. - Cheddar and Gouda Fried Lobster Macaroni & Cheese, Get Maine Lobster

Macaroni and Cheese bites are a great snack as it is, adding lobster would make them even better. - Irish Lobster Macaroni and Cheese, All That’s Jas

I love the concept of individual servings in ramekins, topped with puff pastry. - Lager Macaroni and Cheese, Beer Institute

Because of the lightness of lobster meat, a lighter lager likely works best. - Maine’s Best Lobster Macaroni and Cheese, Lobster Anywhere

I referenced their lobster data above, this recipe includes more information on pasta types and cheeses that are best suited to the dish. - Spicy Lobster Mac and Cheese, Foodness Gracious

Includes Cabot Wickedly Habanero Cheddar and Cabot Extra Sharp Cheddar. - Truffle Lobster Macaroni and Cheese, No Spoon Necessary

Drizzling with truffle oil adds a bit more decadence. I would also shave fresh truffles on top as a final garnish before serving.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Barilla, Academia, 2013, I Love Pasta: An Italian Love Story In 100 Recipes, Newtown, Connecticut; The Taunton Press

- De Salis, Harriet A., 1888, Oysters à la Mode: The Oyster and Over 100 Ways of Cooking It, London, England, UK, and New York, New York; Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Dueland, Joy V., 1973, The Book Of The Lobster, Somersworth, New Hampshire; New Hampshire Publishing Company

- Farmer, Fannie Merrill, 1896, The Boston Cooking School Cookbook, Boston; Little, Brown, And Company

- Farmer, Fannie Merrill, 1921, The Boston Cooking School Cookbook, Boston; Little, Brown, And Company

- Gillette, Mrs. F.L., and Ziemann, Hugo, 1887, The White House Cook Book, Chicago, Illinois; The Werner Co.

- Gillette, Mrs. F.L., and Ziemann, Hugo, 1895, The Presidential Cook Book, Chicago, Illinois; The Werner Co.

- Goodnough, Abby, February 26, 2011, After a Record Haul in Maine, Try the Lobster Mac and Cheese, New York, New York; The New York Times

- Keller, Thomas, 1999, The French Laundry Cookbook, New York, New York; Artisan

- Kirk, Dorothy (Ed.), 1947, Woman’s Home Companion Cookbook, New York, New York; P.F. Collier & Son Corporation

- Leone, Gene, 1967, Leone’s Italian Cookbook, New York, New York; Harper & Row, Publishers

- Levinson, Leonard Lewis, 1964, American Heritage Cookbook and Illustrated History of American Eating & Drinking: Delmonico’s (chapter), New York, New York; Simon & Schuster, American Heritage Publishing

- Martin, Kenneth R., and Lipfert, Nathan R., 1985, Lobstering And The Maine Coast, Bath, Maine; Maine Maritime Museum

- Montagné, Prosper, 1961, Larousse Gastronomique, First English Edition, New York, New York; Crown Publishers, Inc.

- Reeve, Mrs. Henry, 1882, Cookery and Housekeeping, A Manual Of Domestic Economy for Large and Small Families, London, England, UK, and New York, New York; Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Rombauer, Irma, 1931, The Joy Of Cooking, St. Louis, Missouri; A.C. Clayton Printing Company

- Shibles, Loana and Rogers, Annie, 1975, All Maine Seafood Cookbook by Those Who Know Fish, Rockland, Maine; Courier-Gazette, Inc.

- Wise, 1954, The Wise Encyclopedia Of Cookery, New York, New York; Wm. H. Wise & Co., Inc.