Raw Milk

Raw milk for sale in multiple container sizes in the store at Nezinscot Farms in Turner, Maine, on May 22, 2018. The sale of raw milk is illegal in many other states.

In early 2018 my oldest son wanted to start a new hobby making his own cheese. He got everything together and then went looking for unpasteurized milk, aka raw milk, to get started.

But he ran into a brick wall courtesy of the State of Michigan. He couldn’t get raw milk anywhere. And that was the end of it.

On a page titled “What’s the Scoop on Raw Milk in Michigan?“, the state’s Department of Agriculture & Rural Development gives their history of why this brick wall is in place:

“In 1948, Michigan was the first state to require that all milk sold to consumers be pasteurized … FDA banned the interstate shipment of unpasteurized (raw) milk to consumers in 1987, garnering the United States worldwide recognition as having the gold standard for milk safety … The Michigan Legislature reaffirmed this important food safety principle in 2001 when it continued the prohibition on the sale of unpasteurized (raw) milk to consumers … In December 2005, FDA issued a warning advising consumers to avoid drinking unpasteurized (raw) milk due to an outbreak in Washington State and Oregon that was linked to the consumption of unpasteurized (raw) milk contaminated with Escherichia coli O157:H7 obtained by consumers directly from a dairy farm … According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), raw milk is unsafe and should not be consumed. FDA’s position is consistent with that of the American Medical Association stating, ‘All milk sold for human consumption should be required to be pasteurized.”

Beyond the state of Michigan’s information above, at the federal level the FDA begins with these question in its “Questions u0026amp; Answers: Raw Milk“:

1. Is it safe to consume raw milk?

No.

[note: detailed information follows this answer. The next question is …]2. Have any illnesses or deaths been caused by consuming raw milk products?

Based on CDC data, literature, and state and local reports, FDA compiled a list of outbreaks that occurred in the U.S. from 1987 to September 2010. During this period, there were at least 133 outbreaks due to the consumption of raw milk and raw milk products. These outbreaks caused 2,659 cases of illnesses, 269 hospitalizations, 3 deaths, 6 stillbirths and 2 miscarriages. Because not all cases of foodborne illness are recognized and reported, the actual number of illnesses associated with raw milk likely is greater.

There’s no debating the above figures. They’re likely quite accurate.

But let’s get back to Maine.

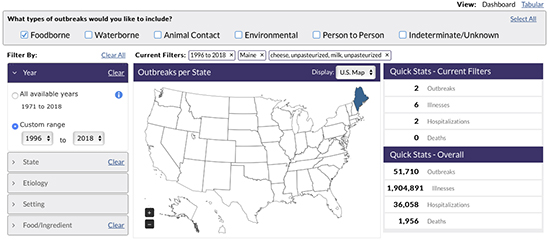

The Centers For Disease Control And Prevention (CDC) maintains what’s known as a National Outbreak Reporting System. Using this tool, a user can “drill down” into seeing Food outbreaks in Maine from 1996 – 2018 (2018 being the latest year for compiled data as of December 4, 2020), then filter to only show outbreaks for “milk, unpasteurized” and “cheese, unpasteurized”. The result is the following screen:

The CDC’s National Outbreak Reporting System Dashboard. The selected filters for the state of Maine, outbreaks related to unpasteurized milk as well as cheese made from unpasteurized milk, result in two outbreaks from 1996 to 2018.

Scrolling down the page, other charts show one outbreak in 1998 and another in 2014. These charts only show outbreaks for raw milk, but none for cheese made from raw milk. That filter can be deleted as there’s nothing there.

At the bottom of the page there’s a link, “Download current search data (Excel)”. Opening that file shows there was an outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 in July 1998 from “other milk, unpasteurized” resulting in two illnesses and two hospitalizations (from the above screenshot the illnesses were those hospitalized), and an outbreak of Cryptosporidium parvum IIaA15G2R1 in January 2014 from “milk, unpasteurized”, resulting in four illnesses and no hospitalizations.

Over fifteen years between very minor outbreaks from raw milk.

So, why is Maine different? Why is the sale of raw milk allowed while keeping outbreaks of illnesses down to being almost non-existent?

On February 8, 2012 Food Safety News published an article, “Portland, ME Says ‘Yes’ to Raw Milk at Farmers’ Markets“. The article includes some interesting information:

“Heather Donahue, co-owner of Balfour Farm and a raw-milk vendor at the city’s Wednesday farmers’ market, told council members that raw-milk farmers are required to inform customers that the milk hasn’t been pasteurized by putting the words ‘not pasteurized’ on the containers’ labels … She also pointed out that while in the past raw milk was a ‘significant’ carrier of diseases, many improvements have been made since then. She said that to be certified as a raw-milk dairy in Maine, the dairy herd has to be tested at regular intervals and strict sanitation practices must be followed … In an interview after the meeting, she told Food Safety News that she was relieved that raw-milk dairies won’t have to display the placard about the potential health risks of raw milk … ‘In general, the people who shop at farmers’ markets know about raw milk and seek it out,” she said. They can get more information from us than they can from a store clerk.’” [Beecher, Cookson. Portland, ME Says ‘Yes’ to Raw Milk at Farmers’ Markets. Food Safety News, 2012.]

It turns out Maine is very specific about doing things their own way. From Maine’s Revised Statutes, section 2902:

§2902-B. Sale of unpasteurized milk and milk products

1. Sale of unpasteurized milk or milk product. A person may not sell unpasteurized milk or a product made from unpasteurized milk, including heat-treated cheese, unless the label on that product contains the words “not pasteurized.”

[ 2005, c. 270, §3 (AMD) .]

2. Sale of unpasteurized milk or milk product at eating establishment. Except as provided in subsection 5, a person may not sell unpasteurized milk or a product made from unpasteurized milk at an eating establishment as defined in Title 22, section 2491, subsection 7.

[ 2009, c. 652, Pt. B, §1 (AMD) .]

…

4. Testing of unpasteurized milk products. The commissioner shall establish a process by rule for submitting samples of unpasteurized milk products to an independent laboratory for testing when:

A. The milk laboratory operated by the department has tested unpasteurized milk products and determined that they do not meet the standards for unpasteurized milk products established by rules adopted pursuant to section 2910; and [2005, c. 172, §1 (NEW).]

B. The person operating the milk plant that processed the milk products has requested independent testing. [2005, c. 172, §1 (NEW).]

Where it gets interesting is when we look at the mentioned section 2010 for standards:

§2910. Standards for milk and milk products

The commissioner, in a manner consistent with the Maine Administrative Procedure Act, shall establish standards by rule for the inspection and examination, licensing, permitting, testing, labeling and sanitation of milk and milk product production and distribution. [1999, c. 362, §15 (NEW).]The standards must be consistent with the requirements of the official standards, known as the Pasteurized Milk Ordinance, as issued by the Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, except that the standards may not prohibit the sale of unpasteurized milk and milk products in the State. [1999, c. 362, §15 (NEW).]

Rules adopted pursuant to this section are major substantive rules as defined in Title 5, chapter 375, subchapter II-A, except that amendments to the rules to maintain consistency with the official standards known as the Pasteurized Milk Ordinance, as issued by the Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, are routine technical rules as defined in Title 5, chapter 375, subchapter II-A. Amendments to the rules may not prohibit the sale of unpasteurized milk or milk products in the State. [1999, c. 679, Pt. A, §12 (AMD).]

“… the standards may not prohibit the sale of unpasteurized milk and milk products in the State” … “Amendments to the rules may not prohibit the sale of unpasteurized milk or milk products in the State.” These statements make Maine’s view on the subject of raw milk quite clear.

Maine has a comprehensive Dairy Inspection Program that accomplishes what Ms. Donahue was talking about in 2012. The University of Maine Cooperative Extension maintains a checklist for those dairies who wish to get into the production of raw milk.

Maine’s approach to raw milk is one of common sense and education. Raw milk isn’t vilified in Maine, as it is by other states and the FDA as well. Instead, it’s enjoyed as it alway has been. Enough safeguards and programs have been set in motion to ensure outbreaks seen in other states are either minimal or don’t occur at all.

Cottage Food Laws

It seems to be getting more and more difficult to operate any kind of food business out of a home. Since I’m originally from Michigan and have wanted to operate a home food business, as well as having restaurant management experience, I’ve looked into what it takes.

The State of Michigan has put together a page on the subject, “Michigan Cottage Foods Information“. The second paragraph reads as follows:

“Under the Cottage Food Law, non-potentially hazardous foods that do not require time and/or temperature control for safety can be produced in a home kitchen (the kitchen of the person’s primary domestic residence) for direct sale to customers at farmers markets, farm markets, roadside stands or other direct markets. The products can’t be sold to retail stores; restaurants; over the Internet; by mail order; or to wholesalers, brokers or other food distributors who resell foods.”

As I was hoping to manfacture and sell my own version of the popular Flint Coney Sauce, I hit a brick wall … another of the state’s brick walls, similar to the laws regarding raw milk.

Further down the page the state gets even more specific:

A producer of Potentially Hazardous Foods/Temperature Controlled for Safety Foods (PHF/TCS) does not qualify as a cottage food operator. “Potentially hazardous food” is defined under the Food Code and is used to classify foods that require time-temperature control (i.e. must be held in a refrigerator) to keep them safe for human consumption. A PHF/TCS is a food that:

Contains moisture (water activity greater than 0.85)

Is neutral to slightly acidic (pH between 4.6 and 7.5)

…

Examples of PHF/TCS foods include:Meat (beef, pork, lamb)

Poultry (chicken, turkey, duck)

Fish

Shellfish and crustaceans

Eggs

Milk and dairy products

Cooked plant-based foods (for example: cooked rice, beans, vegetables, or mushrooms)

Baked potatoes

Certain synthetic ingredients (such as artificial flavoring)

Raw sprouts

Tofu and soy-protein foods

Untreated garlic and oil mixtures

…

Will I need to meet local zoning or other laws?Yes. The Cottage Food exemption only exempts you from the requirements of licensing and routine inspection by the Michigan Department of Agriculture u0026amp; Rural Development. Contact your local unit of government to determine if there are local regulations that will affect your business. Cottage Food businesses also need to comply with the labeling, adulteration, and other provisions found in the Michigan Food Law.

It would almost appear that, in Michigan, the only food products you can make at home are spice blends and dry meat rubs. But even so, you might to mix them while wearing a full face respirator under an industrial hood if that’s what your local county inspectors require. That’s only a minor exageration, scroll down on the state’s page to see some specifics. The code is rather tight.

Let’s head back to Maine.

The basics of Maine’s Home Food Law is contained in four pages. There’s also a four-page application. The May 2018 versions of these documents are below.

Some of this can be difficult to comprehend, so the Maine Federation of Farmers’ Markets has put together their “Farmers’ Market License Requirements“. Part of this page is a list of items which can be made by someone with a home food license:

A Home Food License is required to prepare the following:

* Bakery goods (no cream fillings)

* Jams and Jellies: Traditional Jams/Jellies: Naturally acidic fruits commonly used for jams and jellies containing sugar, pectin and fruit; strawberry, raspberry, blackberry, blueberry or any combination of these berries. When contacting UMaine with a recipe known to be safe, a process review is not necessary. Vendors should request an email from UMaine stating a recipe is safe. Reduced sugar jams and jellies require a process review. UMaine recommends all jams and jellies be submitted for process review to verify that Standards of Identity has been met. Non-traditional jams and jellies and acidified foods must be submitted for a Process Review conducted by a Process Authority (UMaine).

* Acidified Foods, pickles, relishes, sauces. Non-traditional jams and jellies and acidified foods must be submitted for a Process Review conducted by a Process Authority (see above).

* Herbs

* Chocolates and Confections

* Honey (Note: raw honey in the comb does not require a processing license)

This is quite different from what’s allowed in Michigan, and has led to a lot of variety in available locally-made food products. Even so, it’s still a bit shy of what’s been accomplished in Wyoming’s Food Freedom Act of 2015.

Educating The Bureaucrats

Lawmakers are human, as are health inspectors. They make mistakes as anyone else will. It follows then that not all rules and regulations, including those regarding the food industry, will ever be accurate. What this also means is that enforcement isn’t always accurate either, nor does enforcement necessarily mean common sense is involved.

In running restaurants, some of the misinformation I’ve heard in dealing with health inspectors is easily challenged if my own responses involved common sense they can identify with.

Unfortunately more than one instance involved misinformation that tends to drive food fears deeper. Those instances are worth mentioning here.

During the summer of 2008 I operated a hot dog stand at a Michigan beach on the shore of Lake Erie. As we weren’t going to be open but three months, I’d decided to pay for monthly inspections as the three of them together cost less than the one annual inspection. During our first inspection the health inspector called me out for having the raw hot dogs above other items in the cooler, as raw meats belong on the bottom so they don’t possibly contaminate other items below it.

There’s a set order for how raw proteins should be stored on shelves in a restaurant cooler. This is either on one set of shelves in a walk-in, or in a separate small walk-in or reach-in. From the top down:

- Ready-to eat foods

- Raw Seafood

- Raw Whole Meats

- Raw Ground Meats

- Raw Poultry

I had the Koegel Skinless Frankfurters on the top shelf. What she was telling me was that the raw hot dogs needed to be down with the raw ground beef.

I explained to the inspector that, unless there was a hot dog manufacturer in the county I was unaware of, I doubt she had ever seen a raw hot dog. I handed her the package and showed her where it plainly says “fully cooked” on the label. If you click the link above, you’ll see it yourself.

She and I got along fine after that. The other two inspections went well, as I didn’t change how we operated after the initial inspection. But we did have one other almost-heated discussion, which was unrelated to my shop.

I had started designing menus for a local French restaurant and was outide at a picnic table marking a printed rough copy when the inspector arrived one day. She did her inspection then joined me at the table to finish her paperwork. She asked what I was working on and I told her. She then told me the French restaurant was one of her places, which I already knew from seeing her there, and asked if she could see the menu.

It was at this menu item that the conversation went south.

Pork Saltimbocca – Center cut 12 ounce pork rib chop wrapped with prosciutto ham u0026amp; sage leaves and pan seared. Finished in a savory cream sauce with wild mushrooms. Recommended medium-rare unless otherwise instructed.

The medium rare Pork Saltimbocca described above, as it was served on October 15, 2009. Note that it’s a rather quick pan sear, otherwise the prosciutto and fresh sage would burn. The medium rare temperature is necessary to provide this balance.

As early as 1924, the Enyclopedia Americana was recommending safe temperatures of 176°F (77°C) for fresh loin roasts and 185°F (85°C) for other large fresh cuts. This was to fight the occurence of trichinosis, “infection caused by the roundworm Trichinella spiralis or another Trichinella species” (Merck Manual, Consumer Version). In 2008, the FDA was recommending a safe temperature for pork of 160°F (71°C).

Medium rare is 145°F (62.8°C). That’s why our conversation went south.

The health inspector argued that pork couldn’t legally be served below a temperature of 160°F. I argued that pork had gotten considerably safer since my mom had browned chops in a skillet before putting them in the oven to bake, and that I’d enjoyed the Pork Saltimbocca at my friend’s French restaurant at least four times that I could recall and hadn’t become ill once.

The discussion basically ended when she said that didn’t matter, even if she agreed, which she didn’t, there was nothing she could do anyway as the menu had to be approved by the health department and it would be rejected.

But nothing happened. The menu wasn’t rejected. I continued to enjoy the Pork Saltimbocca, ordering it from the same menu I’d designed.

And then an interesting change took place. On May 24, 2011, the USDA lowered their recommended cooking temperature for pork to 145°F, aka medium rare.

The Chef I knew was simply ahead of his time.

Going back to the northeast one more time, Chef Matthew Secich opened Amish Charcuterie in Unity, Maine, in 2015. The Chef had made a name for himself in better restaurant kitchens already, including being a sous chef at Charlie Trotter’s in Chicago. He’d left that lifestyle to make handmade charcuterie using old-fashioned techniques and offer them directly to the public.

That’s how he ran into trouble with the state of Maine. On March 26, 2016, Reason published an article by Food Law & Policy Attorney Baylen J. Linnekin, author of “Biting the Hands that Feed Us: How Fewer, Smarter Laws Would Make Our Food System More Sustainable“. In the article, titled “Maine Food Rules Handcuff Amish Sausage Maker“, Linnekin described how the state of Maine came close to shutting down Amish Charcuterie because Secich wasn’t following the Maine Food Code, specifically the lack of an HAACP plan, and the use of an icehouse for chilling food.

As Linnekin pointed out:

“… Charcuterie’s icehouse either is chilling food properly or it’s not. And there’s been no suggestion by [John Bott, a spokesman for the Maine Department of Agriculture, Conservation, and Forestry] or other state officials that it’s not. That makes sense, since … ice can cool food at least as well as does mechanical refrigeration.”

Throughout the article, Linnekin gives excellent examples of regulators and inspectors responding to laws instead of common sense, including a discussion of how Maine had seized “hunderds of pounds of … cured meats from restaurants in the state” which “have been embargoed by health officials and are waiting in cold storage until restaurants can prove the food is safe”. Note how that reads. The state of Maine hadn’t proved the meat was bad to begin with. But they wanted proof it was safe.

By the end of the article, Linnekin was reporting “… new set of inspectors visited Secich and, he says, pledged to work with him to find a way forward”. As of May 2018 Amish Charcuterie was reported to still be open.

Raw Ground Beef Traditions

In Wisconsin one of the popular holiday meals is referred to as either a Cannibal Sandwich or Tiger Meat. According to the Wisconsin Department Of Health Services:

Since 1986, eight outbreaks have been reported in Wisconsin linked to eating a raw ground beef dish, including a large Salmonella outbreak involving more than 150 people during December 1994. Ground beef should ALWAYS be cooked to an internal temperature of 160° F.

A serving of Steak Tartare I enjoyed on March 9, 2007, without becoming ill in any manner.

These claims by the Department completely ignore the safe existence of Steak Tartare, Kibbie Nayyah which is raw ground lamb or goat, or other dishes of ground raw red meat that are honestly quite safe to eat. Instead, it pushes the false narrative that only their rules apply vs. the known safety of what are in many instances centuries of tradition, especially in Mediterranean cultures. Knowledge-based education would be a better alternative, such as including experienced chefs and butchers in making sure the public knows how to prepare these traditional dishes using the right cuts of meat. Otherwise, no one will listen, and the Department will continue to appear ludicrous.

Conclusion

Contrary to information from the FDA and other agencies at the federal level, Maine is a clear example that fear-mongering about certain foods at the state level isn’t necessary. With the sections of Maine’s Revised Statutes regarding the production and sale of unpasteurized milk, as with the state’s Home Food Law, both knowledge-based education and common sense prevail. Because of education and inspection programs, outbreaks related to raw milk, as it’s commonly known, are quite far below CDC national data. This could be a model for national legislation, if such legislation were to ever occur.

Fears about foods shouldn’t come from the state or federal agencies. That’s the real lesson here.